Residential Property Appraisal in 2022.

As we move into the new millennium, evidently the pace of change is increasing all the time. The surveying profession has to respond to the challenges if it is to continue to play an influential role in the property industry of the 21st century. Various catalysts are currently influencing the direction of this profession and in respect of residential property they include:

- the government are looking to make home buying easier through the establishment of ‘Vendors Surveys’ and other initiatives;

- the RICS has an ‘Agenda for Change’;

- through new technologies the tools are now available to facilitate change in a way never experienced before.

This book looks at the core skills that a surveyor needs to carry out appraisals of residential properties in a changing world. It is not restricted to experienced surveyors alone. The book is written in a way to encourage the student/trainee from whatever background to develop the skills associated with inspecting the residential home.

Looking back over the last ten years it is clear to us why there is a need for this book. We have been involved with organising, producing, delivering and evaluating training events for all kinds of Chartered Surveyors and other professionals involved in the appraisal of residential property. The events have included seminars, workshops and conferences for both in-house staff groups and independent surveyors attending speculative continuing professional development (CPD) sessions. The one enduring impression is that technical topics are always very popular. This is not because participants want to achieve their allocation of CPD. We suggest there are other reasons for this popularity:

- The focus of the knowledge and experience of many professionally qualified surveyors has been closely associated with the valuation of property and not its physical state. On the other hand the building surveyor or other similar qualified professional’s focus is the reverse of this. Few courses have catered for the equal combination of skills.

- Many educational courses lack a sound technical grounding. The professional institutions often call for broader, more flexible surveyors armed with business and commercial skills. As a consequence, a number of traditional disciplines have disappeared from the curricula. Building studies and building defects are two such subjects.

- Technical advice and guidance that are currently published have a broad audience. A lot of literature is specifically written for those who carry out in-depth surveys and investigations of residential property. It is often difficult to identify which part of this advice is best suited to the professional practice of residential valuation and appraisal.

- Many of the recent court cases that have struck fear into the hearts of surveyors have been associated with disputed technical assessments of dwellings. This may have added to the sense of collective professional inadequacy!

To try and meet this demand and plug the skill gaps, the authors have had to rewrite, interpret or specially create training materials that match the professional role of the participant surveyors. Many commentators that write or lecture on technical matters appear to consider that the sole purpose of residential valuations and surveys are to correctly diagnose every hidden defect in every dwelling. Alternatively the less technical standard guidance tends to concentrate on procedure and process, offering little in the way of practical detail.

In addition there are two other sources of change that are appearing on the horizon:

- The structural changes of many lenders have resulted in different business priorities. New technology has revealed opportunities not available previously and exposed different working practices abroad that could be imported to this country. The structure of the residential market in countries like the USA, Australia and New Zealand is much less complex and uncertain. As the global economy has a greater influence on the domestic market and more financial institutions operate internationally, pressure will be applied to simplify the process.

- Customer expectations are changing. The typical ‘customer’ is becoming far more sophisticated. They are better educated and used to more customer-focused service in all the ‘other’ products they purchase. Evidence from consumer surveys, media sources and pressure groups suggests that the standard of service that many surveyors provide falls well below current expectations.

This book sets out to meet these challenges. What is needed is a publication that has a clear technical focus directly related to the professional role of its readership. Because this role is closely associated with value, then part of the book must acknowledge the actual process of valuation. Because the commercial world is never static all this must be set against a backcloth of change and increasing expectations from the people who matter – the fee payers!

Objectives

Based on this contextual review, the objectives of this book are as follows:

- to provide surveyors with sufficient practical and detailed information so the condition of residential dwellings can be appropriately assessed. In this case ‘appropriately’ would equate to the standard currently expected of the Mortgage Valuation and Homebuyers Survey;

- to help surveyors further develop the skills of communicating the results of these assessments to their customers;

- to provide an overview of the valuation process with a particular emphasis on how the condition of a property affects its value;

- to highlight the changing nature of the residential property appraisal process and initially identify some of the techniques and mechanisms that may help surveyors adapt to this changing environment.

Definitions

Clearer definitions of the principle terms employed in this book may be useful: Residential property – any property that is used as, or is suitable for use as, a residence. This book is restricted to domestic dwellings owned by an individual(s) who relies on finance obtained from a commercial lending institution.

Residential appraisal – an act or process of estimating the value, worth or quality of a residential property.

Customer or client – in this book these two terms are used to describe the end user of any survey or inspection report and will usually be a private individual.

Surveyors – this generic term has been used to describe Chartered Surveyors.

Who Is It For?

This book has been written for a broad range of surveyors whose primary interest is with the appraisal of residential property. The book assumes that the reader:

- has already or is close to satisfying the academic requirements of their chosen professional institution. This would have included a course of study that introduced participants into how dwellings are designed and constructed and the principle agents responsible for the deterioration of the building fabric, and;

- has had some professional experience of assessing a range of different properties.

In terms of qualifications and level of experience, this book should be suitable for:

- student general practice surveyors in the later stages of their academic course or are on the sandwich placement or year-out stage;

- building surveying students in earlier stages of their education who are looking for an introduction to the assessment of residential properties;

- students on courses of a more specialised technical nature such as NVQ or HND routes that need an understanding of how to carry out an appraisal of residential property;

- surveyors that are working towards their professional assessment and need to refer to written guidance and technical information on a regular basis;

- those more experienced surveyors who may be changing their professional emphasis away from solely valuation activities to the more challenging pre-purchase surveys;

- qualified and experienced surveyors that need to carry around a source of reference so they can refer to standard guidance when novel situations are encountered.

The Philosophy

The guidance contained in this publication aims to be challenging to the reader in two ways:

- to outline processes and techniques that may potentially take the surveyor beyond the parameters of current standard surveys. This will enable surveyors to more effectively provide those services and better cope with any changes to standard practice in the future;

- to engage with the surveying process and positively advise clients about the suitability of their potential new home. The book is a challenge to ‘defensive surveying’ and encourages surveyors to focus on the client’s needs rather than protecting their own liability.

This book is not a guide to any particular standard form of survey promoted by any particular professional institution. For something more specific then the reader should refer to the publisher of the particular product.

Technical content – a cautionary note

In an effort to achieve the objectives set out in section 1.2 a massive amount of technical information has been included in this book. This includes such things as indicative joist and rafter sizes, typical ratings for boilers and average ventilation values for airbricks. Every effort has been made to use up-to-date and accurate information but standards and regulations change over time and soon outdate publications like this. Additionally, the authors have purposely ‘summarised’ some of the technical guidance in a pragmatic effort to give surveyors digestible and broad-brush guidance that can help them make judgements on an everyday basis. Therefore, if more precise guidance on specific topics is required then please refer to the documents identified in the reference section at the end of each chapter.

Contents

The book is split into three parts:

- Part I – this part provides an overview of the valuation process itself. Particular emphasis is placed on the role of condition in determining value. This part also contains advice about how to approach and carry out a survey.

- Part II – this is the main focus of the book and so is the largest part. It covers all the defects normally associated with residential property and outlines a strategy to resolve these problems.

- Part III – the main practical guidance relates to good practice in report writing. This includes a number of case studies to illustrate both good and bad practices. The part finishes with an assessment of how professional practice in this area may change in the future and suggests a few strategies for turning these threats into opportunities.

The Appraisal Process.

In the case of Roberts v. J. Hampson & Co (1989) Ian Kennedy described an important aspect of a Building Society Valuation:

It is a valuation and not a survey, but any valuation is necessarily governed by condition.

Consequently this book will focus on those residential valuations and surveys where condition plays a key role.

This chapter will look at the appraisal process for residential property of which valuation forms a key part. It will do this by reference to basic definitions and then review the Comparable Method of valuation which is one of the common techniques used. The focus of this chapter is also to develop the more scientific approach as this removes some of the subjectivity from the results. It will never be possible to produce a black and white solution, but hopefully this approach will narrow the ‘grey’ areas.

Anyone undertaking a valuation of property for any credible purpose should have working knowledge of the RICS Appraisal and Valuation Manual (RICS 1995), in association with the Incorporated Society of Valuers and Auctioneers and the Institute of Revenues Rating and Valuation, or otherwise known as the ‘Red Book’. Unlike this key reference manual, this book attempts to help the inexperienced and to give an insight into the methodology necessary to achieve a competent appraisal of residential property.

An appraisal usually takes place when a property changes ownership but the form of advice may vary. This depends upon whether the parties to the transaction are buyers, sellers, estate agents, conveyancers, financial intermediaries or lenders. An underlying theme is establishing whether it is a good deal for them. For example, the buyers want to know if it is good value for money and whether they will get a mortgage. The seller, on the other hand, wants to know what is the highest price that the property will sell for. The lender is more likely to want to know what is the most realistic price that can be achieved on resale and what is the risk associated with achieving that resale. This publication concentrates on the form of advice that those parties may need by specific reference to the condition of the property. It is for the practitioner to establish the precise needs of the client and to provide the advice in the form requested.

An overview

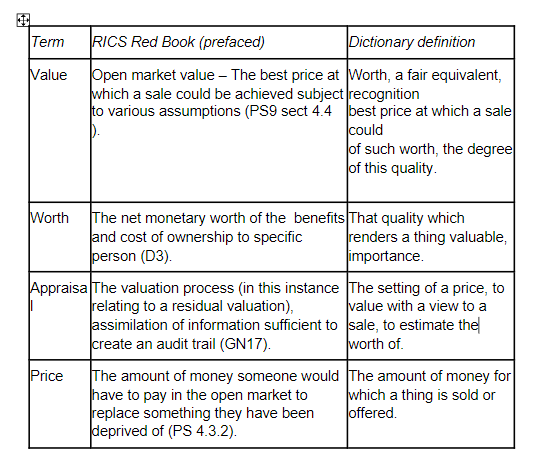

To begin with it will be useful to briefly review the meaning and interpretation of the key words by reference to the Red Book (1995). It refers principally to commercial property and therefore it has been necessary to interpret the concepts for residential property. To assist in this process the dictionary definitions of a number of terms that appear in the Red Book are compared (see figure 2.1).

The linkage between all these terminologies is that the surveyor must go through a recognised process (the appraisal) to accumulate information that is sufficient to establish the property’s relative quality (value) and its specific range of benefits to the client (worth). This is so a monetary figure can be attributed (price) which could be considered as compensation should the client be deprived of those benefits.

Market forces ultimately determine price and the surveyor interprets which ones will govern that figure. How this is done depends on the client because different clients will gain different benefits. Numerically, the two most featured clients to a transaction of residential property are the lender and the buyer who both have an interest in its future saleability.

The experienced surveyor may well produce a figure for a property that fairly reflects market value intuitively. In the background is a complex process of comparison that is done almost subconsciously. The basis of that analysis is explained in section 2.3 but valuing intuitively can be accounted for through the process of expertise acquisition (see chapter 3). This section will be of particular relevance to newly qualified surveyors but it is hoped that even those more experienced may find this approach a stimulus to review their existing practices and reflect whether they meet current-day needs!

The Lender ’s View.

At the time of writing there is a fundamental change taking place in how lenders view property as a security for lending purposes within the UK. For many years Building Societies legislation governed the procedure that had to be adopted when valuing a property for mortgage purposes. This covered the majority of transactions and required a valuation for all property to ensure that it provided a reasonable security for the loan. Any factors that materially affected the valuation had to be reported. This still applies but for those lenders that fall outside the legislation (i.e. banks, etc.) there is an increased emphasis on the customer’s ability to repay the loan. Ensuring the property forms a good security can be of secondary importance. This is especially true for the increasing number of overseas lenders who are more comfortable with this ‘customer approach’. As a consequence the emphasis on the valuation report has changed.

This can be illustrated by the changes in inspections associated with the sale and purchase of property. A few years ago there were only main three types:

- the mortgage valuation

- the Homebuyers report (now known as the Homebuyers Survey and Valuation, licensed by the RICS and ISVA)

- the Building Survey.

Figure 2.1 Comparison of key valuation terms.

More recently there has been an increase in alternatives to the ‘Homebuyers report’. Additionally there has been an increase in the use of desktop and drive-past assessments. Although these have always been used on a small scale, recent changes may result in an increase in use.

Without an internal inspection it is impossible to provide a valuation within the meaning of the Building Society legislation. However, those lenders that fall outside of this do not need a valuation especially where the loan is relatively low compared with the transaction price (say 60%). In these cases, the lender merely needs to establish that:

- the property falls into the estimated price bracket, and;

- there appears to be acceptable risks.

In some cases the loan may be covered by the value of the land alone. So as long as the land exists the lender need not make any further inquiries. The legal process alone can often establish this fact. The use of a property database may also give sufficient assurance that the value is, in all probability, realistic. Because this book focuses on the condition of the property being appraised, the forms of assessments that do require an internal inspection are not considered any further.

Despite the recent change in emphasis, condition is still seen as the major area in the process of determining whether the value is sustainable. It is still the most commonly reported and often provides a pre-condition to the loan.

The Purchaser ’s View.

The purchaser should have a wider view than the lender although this is not always the case. A significant proportion of customers assume that if the lender is satisfied with the property as security for a loan then so should they be. This was confirmed in the case of Smith v. Eric S Bush (1990) where Lord Griffiths stated among other things that:

If the valuation is negligent and is relied upon damage in the form of economic loss to the purchaser is obviously foreseeable. The necessary proximity arises from the Surveyor’s knowledge that the overwhelming probability is that the purchaser will rely upon his valuation. The evidence was that surveyors knew that approximately 90% of purchasers did so and the fact that the surveyor only obtains the work because the purchaser is willing to pay his fee.

This clear ruling has been slightly clouded, as the purchaser will not always pay a fee, as some lenders do not make a charge directly. Because the surveyor will still be paid, the debate will continue. If the cost of the survey is included within the cost of the mortgage, does the purchaser pay it indirectly? The recent move by some lenders to non-disclosure of reports places purchasers in a further dilemma. Can they continue to rely on the action of the lender? There may be a significant difference between the loan and the purchase price. This margin can accommodate a wide range of deficiencies in the property that may in some cases cost many thousands of pounds to rectify. Purchasers may be very disappointed with this gap between the lenders’ criteria and their own expectations. Any disgruntled purchasers might be denied remedies in law. If this is the case they will remain disillusioned with the professional who provided that report as well as that person’s professional Institution. To counteract this, professional organisations associated with the sale and purchases of property have mounted a campaign to educate the public. They urge people to obtain reports that more fully advise about the factors that will affect their decision to purchase. Such a report requires more detail than that provided by the lender’s own surveyor. Appreciating that this is not the only approach the RICS have launched the Agenda for Change to encourage the surveying profession to adapt to the needs of the customers. In addition the Government has launched a campaign to make home buying easier.

Future Issues.

Do surveyors’ reports address the key points that are important to the lender? The lender assesses a loan on the basis of the borrower’s ability to repay. However, there is also the fall-back of what is the probability that it will be possible to realise the money on loan should this prove necessary.

The property is only a part of that equation but a significant one hence the reason for the variations in views by some lenders. Take the comparison with a company making a loan on a car. They do not ask for a survey of the car so why should they with a property? It is clearly the purchaser of the car who needs to be sure that the car can perform as sold. The lender only needs to know that the borrower can pay. A property is a major investment to an individual, but should the protection be legally enforced? For this reason it is suggested that there is a clear change of emphasis at the present time. This may of course change.

The problems of negative equity experienced in the late 1980s early 1990s clearly identified a shortcoming within the existing valuation process. Predicting market movements or anticipating a change in price prove to be very difficult. A lot of work has been undertaken on statistical analysis of the housing market both in America and the Pacific Rim but in this country the analysis has generally been retrospective. The ability to forecast accurately is an extremely complex process, especially when global

influences on economies have to be taken into account. So it is hardly surprising that the local valuation surveyor struggles with some of the modern-day aspirations.

The Valuation Process.

The definitions of value for mortgage purposes have changed over time. The current one is known as Open Market Valuation. The other types are noted in the most recent edition of the Red Book and include Estimated Realisation Price (ERP), Estimated Restricted Realisation Price (ERRP) and Market Value (MV). It is important to clarify the type of valuation that is most appropriate to the work being undertaken. Before the various nuances of the valuation definitions can be discussed there are a number of basic principles associated with the valuation process that must be understood.

The appraisal process for residential property consists of a number of stages:

- collection of relevant information

- inspection of the property and its environment

- an interpretation of the extent and nature of the interest

- measurement of development potential or general enhancement of the property to maximise its benefits

- market analysis

- calculation of price/value/worth.

These may appear to be a complex series of questions that would take a significant amount of time to complete. In reality for a mortgage valuation it can take on average 30–45 minutes and for a ‘Homebuyers Report’ 2–3 hours. The experienced surveyor may find it difficult to recognise the individual stages in the process, as so much of it will be done subconsciously. Also, in the majority of cases the property will meet the normal expectations. In other words fewer investigations will be needed, speeding up the appraisal process even further. Each of these factors will be considered in turn.

Collection of Relevant Information.

It is a requirement of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) that corporate members should be able to demonstrate that they have good local knowledge of a particular type of property and the market. Consequently the surveyor should have access to a comparable record of residential property transactions. The size and nature of this record will vary but should have reference to some of the key attributes that will affect the value. These headline attributes are given below (Rees 1992):

- location

- accommodation

- type of property

- the state of repair, appearance and quality of finish

- the quality and quantity of fixtures and fittings

- the potential for improvement

- the supply and demand for property at a point in time

- the exposure of the property in the market place.

The term ‘attributes’ can be defined as:

- characteristics

- the qualities of a property and its immediate environment

- its positive and negative features relating to the market in which the property is based

- legal aspects that affect the benefits for the owner/occupier.

Additionally, within each of these there are other important factors. For example, under ‘type of property’:

- size of property

- the dwelling’s attachment, e.g. semi-detached, detached, terrace, etc.

The relative importance of each one of these attributes may vary considerably between different geographical areas:

- Character of location can play an overriding role regardless of type of property.

- School catchment areas may influence price regardless of other characteristics.

- Number of bedrooms is probably the key attribute within the accommodation section within the UK.

Usually only limited information is recorded and the analysis hinges on the interpretation of how those attributes combine. This is done by identifying those circumstances that differ from the norm (or the surveyors’ expectations of it). In essence the surveyor must be able to record the key attributes of comparable properties so that a full evaluation can take place on-site. Knowing what information to collect is based on a sound understanding of what you are trying to achieve at the outset, i.e. comparison of the subject property with those that are:

- in a similar location

- similarly designed

- in a similar condition

- having similar amenities

- in similar market conditions.

The best comparisons have established values. Therefore the collected information is used to establish the differences between the subject property in its location from the best comparisons known to the surveyor that have been sold in the open market at a point in time. The next step is to determine how important those differences are.

The process does not start at the property but by considering whether anything has changed both nationally, regionally or locally since the last inspection. This may include the density of ‘For Sale’ boards or on a more macro scale a change in interest rates. So information collection starts by reading local and national newspapers.

Special factors may also impact upon the price. The information given to the surveyor at the outset may not include details of why the property is being bought. A simple example is where someone is moving to be close to a new job. Moving to be close to a family member is another example that may not be as common. This may result in the individual paying more for that particular property in order to be sure of getting the location. This may produce a figure in excess of the general market value and therefore may not be repeatable. Regrettably this level of detail may not be apparent to surveyors as their only personal contact is often limited to the vendor.

How To Use The Information.

Having determined what the objectives are for collecting the data, the next stage is to collect the key attributes of the property, as identified previously. It is important to record any issues that are unique to the property. The reasons for this can be listed as follows:

- An experienced surveyor will have in mind a comparison for the subject property. The similarity will be based upon the expertise of the surveyor and the quality of the existing records. The process will involve an objective and subjective ranking. Referring to established scores for each of the key attributes does this. Generally this is done without consciously thinking. A few comments are made in site-notes usually where there are deviations from the norm.

- The collection of data adds to existing records and the knowledge base of the surveyor.

In addition it is important to establish those features within the property that require enhancement to bring the dwelling up to the expected standard for its type and age. Where the clients are known and the surveyor has had the chance to evaluate their needs then an on-site assessment that measures the real or potential benefits to that client would also be significant.

The process can be summarised as:

- collection of data to use for comparison purposes

- a ranking of the attributes and assessment of them by reference to existing comparables

- identification of defects and enhancement potential

- evaluation of the match between inherent benefits and client needs.

In essence the surveyor has to determine where the subject property lies within the range of the comparables for which he has knowledge. So in the context of the scale shown in figure 2.2 property comparisons may fill the whole range from poor to excellent, and more likely they will be nearer the average. It is for the surveyor to establish whether the subject property is better or worse. An added complication is when there are a variety of factors, some of which are better and some worse. In these instances remember to keep it simple. Map out all those factors that are better and those that are the same or worse – imagine them on a scale like figure 2.2. More help is given with this technique later.

Figure 2.2 Scale of comparison for different properties. The key to successful valuation is correctly placing the property on a relative scale.

An Interpretation of The Extent and Nature of The Interest.

There is a whole series of specific attributes that can best be described as those issues that affect the client’s rights to use the property. These may be either to the advantage or disadvantage of the client and consequently will influence the value of the property generally and the worth to the client. These include:

Tenure – the legal right to use the land. This can be freehold or leasehold in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. A feudal arrangement exists in Scotland. The property may be subject to certain forms of ground rent, service charge or chief rent. The impact is that this is an additional cost on the right to use the property. The amount and the conditions surrounding the charge will vary and some will be significant in arriving at the value. There are numerous books on Property Law that will give the legal background and Mackmin (1994) gives a useful interpretation from the surveyor’s viewpoint.

Planning issues – rights under the planning legislation convey the parameters under which the owners can legitimately use or develop the land and its property, for example residential or commercial occupation. In addition they govern the design and safety standards to which a property has to be constructed, whether for new construction or adaptations of the existing structure or appearance. The right to convert land used for agricultural purposes to residential would usually add significant value as the return is greater. On the other hand a restriction on use may adversely affect value (see chapter 13 for more details).

Rights of light, way and other easements or covenants – legal rights defined in the deeds to the original purchase. They can be modified over time and they can be restrictive. Examples could include:

- where a developer and the planning authority agree to an open plan estate that restricts the development of hedges or walls;

- where rights were given allowing a person access to a piece of land over someone else’s property. The initial grant might have been given in exchange for some form of consideration to reflect the adverse impact of the access. Subsequent sales will need to reflect that impact.

The overall impact of these restrictions may be to the benefit of an area as a whole. For example a right of way gives access to many but limits the use to an occupier. The benefit may need to be reflected in valuing neighbouring property.

Environmental considerations – this might be another aspect that could influence value. This covers a wide range of factors varying from climatic conditions to previous contamination of the site. Again the situations can be either beneficial or adverse in that they can enhance or detract from the value. Climatic conditions will feature in various parts of the condition section and reference is made to contamination because of the need to ensure correct site treatment to prevent escape of the contaminant (see chapter 11). The latter aspect poses additional costs in the original construction that may well not be capable of being reclaimed through the sale price when compared with other developments without the contamination. In these cases the developer may choose not to build property until profit margins allow.

All of the features described above may not be apparent from a site inspection of the single dwelling. Reliance is often placed on the conveyancer to unearth any matters that may adversely affect price or value. The surveyor should be aware that the conveyancer is depending on him/her to act as the ‘eyes and ears’ to identify a ‘trail of suspicion’. Consider the following example. There are many large blocks of flats in Greater London, some of which have leisure complexes. The right to use the complex can be included within the deeds, in some cases it is not. Some leases make an additional charge for this benefit. The conveyancer will be depending on the surveyor to identify whether there is a leisure complex. This sounds straightforward. But because a lease can extend over more than one block and can include hundreds of flats the task of locating a fitness gym hidden away in a basement might not be that easy. In one particular instance a purchaser knew about a complex and assumed that the right to use it was included in the purchase. In the event, the complex did not appear in the deeds and the surveyor did not mention it. The potential for a legal challenge by a disappointed purchaser would be a distinct possibility. As the customer rarely talks to the surveyor and the surveyor rarely talks to the conveyancer such a breakdown in communication is bound to happen.

Market Analysis.

This highlights all the factors or attributes that make up the proposition by comparison to the current state of the market. The most important aspect is the local market but this should not ignore macro considerations. The general state of the economy must be accounted for as well as indicators of trends within the housing market taken from leading parts of the country such as London. For example, to slow down the economy over the last decade the interest rates were raised. This did have an important influence on the whole property market. The extent and timing were difficult to anticipate. Local conditions such as the closure of key businesses may have an impact upon the local market contrary to conditions at a national level. The ability of the work force to find alternative employment without moving location is a key determinant of the impact. The introduction of a regular analysis of the economy by the RICS is an indicator of the relevance of this topic and increasing expectations of the customer.

Generally the surveyor undertakes the analysis of the market, based on retrospective information. This poses significant problems, as this information does not forecast what will happen in the future. The surveyor has to anticipate what will happen to the property especially with regard to condition. This provides a useful comparison between the effect of condition on value (a tangible) and those factors of a more subjective nature such as micro and macro economic forces and their influence on value (intangibles). Identifying faults in design or structural elements will lead the surveyor through a process resulting in a recommendation to undertake repairs at a cost that can be deducted from an estimation of price. Considering experience of similar conditions, the risk to the property can be fully assessed and the surveyor can be fairly certain of the outcome. It is different with the economy as a whole. The chain of events that can trigger a recession within the property market either nationally or locally can be very complicated. They have been poorly analysed in the past so it is difficult to be as confident. This should not be used as a catch-all excuse. In Corisands Investments Ltd. v. Druce & Co. (1978) the surveyor was found negligent for not allowing for the speculative element in the property market. The judge based his decision on what ‘an ordinary competent surveyor’ would have done. The test of reasonableness will usually apply. The case of South Australia Asset Management Corporation v. York Montague Ltd. (1996) limited the valuer’s liability to the extent of the overvaluation, known as the SAAMCO cap. As a consequence a valuer cannot be held liable for a downturn in values resulting in the lender making a loss, provided the valuer was not asked to anticipate the changes in the market place and there was no evidence at the time of the valuation of a downturn. In simple terms if a valuer considers a property worth £100,000, but at the time of the value the comparable evidence suggests it is worth £50,000 then the valuer can be held liable. However, if the property was worth £100,000, but as a result of a downturn in the property market, it was subsequently worth £50,000 then the valuer would not be liable.

Basic market forces cannot be ignored but these are not neatly packaged as with other commodities. Property is not homogeneous and records of sales experience throughout an area (beyond the limits of an individual firm) are generally poor. Developing a pattern of supply and demand even at the local level is therefore not a precise science. Anticipating future demand for a specific property has to be based on demand at that point in time and the number of similar products available that will be in direct competition. Consequently the clients take an inherent risk with any property transaction in respect of the intangibles. They cannot be sure that they will receive full compensation if deprived of their benefits at a time when the prevailing market conditions differ from those when the initial transaction took place. Lenders usually take out a form of indemnity to cover large loans relative to value.

The key features of the market analysis are summarised in figure 2.3. No evaluation of the market place would be complete without some consideration of the consumer. In many cases the surveyor may not even be aware of the actual purchaser and is more concerned with the lender. Generally trends develop where consumers of like minds and financial circumstances tend to be attracted to particular areas. This has resulted in a variety of consumer-based statistical surveys being undertaken by companies such as Acorn. The base information for these databases is the census although other types of information may support them. The approach is to evaluate socio-economic groupings based on postcode. Companies needing marketing advice to target areas for specific product sales use the information produced. Essentially these surveys will give an indication of the typical lifestyle for someone living in a certain area. Further investigation can reveal what products that particular lifestyle will want to buy and target them with sales campaigns accordingly. These companies are well positioned to expand this data to provide value comparisons.

Macro economic forces;

Local supply and demand;

Consumer preferences;

Retrospective nature of valuation;

Point in time transactions.

Figure 2.3 A summary of key considerations involved in a market analysis

A further point that is of some significance in the residential market is the availability of finance especially with a highly competitive mortgage market. There was a period when Building Societies had strict limitations on who should receive funds based upon their own limited availability of finance. This put a brake on housing transactions. Once this was removed competitive pressures in the mid-1980s introduced a level of flexibility into the gearing on an individual’s income and innovative ways were found to finance the spiralling house price inflation. Some commentators indicated that this availability of finance was fuelling the inflation. The ability to pay was not such a restricting feature in the equation with the ‘Yuppie’ era of spiralling wage inflation and a willingness of individuals to take on more debt. The philosophy of ‘buy today and pay later’ regrettably came home to roost. By the early 1990s there was a significant rise in repossessions and bad debts, with negative equity introduced into the homeowners vocabulary: it became clear that the property boom could not be sustained.